1.2 Simulations and Animations: "world.ss"

| (require htdp/world) |

This teachpack is deprecated. Use 2htdp/universe instead. See the Porting World Programs to Universe section for information on how to adapt old code to the new teachpack. |

Note: For a quick and educational introduction to the teachpack, see How to Design Programs, Second Edition: Prologue. As of August 2008, we also have a series of projects available as a small booklet on How to Design Worlds.

The purpose of this documentation is to give experienced Schemers a concise overview for using the library and for incorporating it elsewhere. The last section presents A First Example for an extremely simple domain and is suited for a novice who knows how to design conditional functions for symbols.

The teachpack provides two sets of tools. The first allows students to create and display a series of animated scenes, i.e., a simulation. The second one generalizes the first by adding interactive GUI features.

1.2.1 Simple Simulations

| (run-simulation w h r create-image) → true |

| w : natural-number/c |

| h : natural-number/c |

| r : number? |

| create-image : (-> natural-number/c scene) |

| (define (create-UFO-scene height) |

| (place-image UFO 50 height (empty-scene 100 100))) |

| (define UFO |

| (overlay (circle 10 'solid 'green) |

| (rectangle 40 4 'solid 'green))) |

| (run-simulation 100 100 (/ 1 28) create-UFO-scene) |

1.2.2 Interactions

An animation starts from a given “world” and generates new ones in response to events on the computer. This teachpack keeps track of the “current world” and recognizes three kinds of events: clock ticks; keyboard presses and releases; and mouse movements, mouse clicks, etc.

Your program may deal with such events via the installation of handlers. The teachpack provides for the installation of three event handlers: on-tick-event, on-key-event, and on-mouse-event. In addition, it provides for the installation of a draw handler, which is called every time your program should visualize the current world.

The following picture provides an intuitive overview of the workings of "world".

The big-bang function installs World_0 as the initial world; the callbacks tock, react, and click transform one world into another one; done checks each time whether the world is final; and draw renders each world as a scene.

World any/c

For animated worlds and games, using the teachpack requires that you provide a data definition for World. In principle, there are no constraints on this data definition. You can even keep it implicit, even if this violates the Design Recipe.

| (big-bang width height r world0) → true |

| width : natural-number/c |

| height : natural-number/c |

| r : number? |

| world0 : World |

| (big-bang width height r world0 animated-gif?) → true |

| width : natural-number/c |

| height : natural-number/c |

| r : number? |

| world0 : World |

| animated-gif? : boolean? |

| (on-tick-event tock) → true |

| tock : (-> World World) |

A KeyEvent represents key board events, e.g., keys pressed or released, by the computer’s user. A char? KeyEvent is used to signal that the user has hit an alphanumeric key. Symbols such as 'left, 'right, 'up, 'down, 'release denote arrow keys or special events, such as releasing the key on the keypad.

| (key-event? x) → boolean? |

| x : any |

| (key=? x y) → boolean? |

| x : key-event? |

| y : key-event? |

| (on-key-event change) → true |

| change : (-> World key-event? World) |

| (define (change w a-key-event) |

| (cond |

| [(key=? a-key-event 'left) (world-go w -DELTA)] |

| [(key=? a-key-event 'right) (world-go w +DELTA)] |

| [(char? a-key-event) w] ; to demonstrate order-free checking |

| [(key=? a-key-event 'up) (world-go w -DELTA)] |

| [(key=? a-key-event 'down) (world-go w +DELTA)] |

| [else w])) |

MouseEvent (one-of/c 'button-down 'button-up 'drag 'move 'enter 'leave)

A MouseEvent represents mouse events, e.g., mouse movements or mouse clicks, by the computer’s user.

| (on-mouse-event clack) → true |

| clack : (-> World natural-number/c natural-number/c MouseEvent World) |

| (define (create-UFO-scene height) |

| (place-image UFO 50 height (empty-scene 100 100))) |

| (define UFO |

| (overlay (circle 10 'solid 'green) |

| (rectangle 40 4 'solid 'green))) |

| (big-bang 100 100 (/1 28) 0) |

| (on-tick-event add1) |

| (on-redraw create-UFO-scene) |

1.2.3 A First Example

1.2.3.1 Understanding a Door

Say we want to represent a door with an automatic door closer. If this kind of door is locked, you can unlock it. While this doesn’t open the door per se, it is now possible to do so. That is, an unlocked door is closed and pushing at the door opens it. Once you have passed through the door and you let go, the automatic door closer takes over and closes the door again. Of course, at this point you could lock it again.

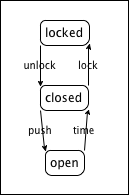

Here is a picture that translates our words into a graphical representation:

The picture displays a so-called "state machine". The three circled words are the states that our informal description of the door identified: locked, closed (and unlocked), and open. The arrows specify how the door can go from one state into another. For example, when the door is open, the automatic door closer shuts the door as time passes. This transition is indicated by the arrow labeled "time passes." The other arrows represent transitions in a similar manner:

"push" means a person pushes the door open (and let’s go);

"lock" refers to the act of inserting a key into the lock and turning it to the locked position; and

"unlock" is the opposite of "lock".

1.2.3.2 Simulations of the World

Simulating any dynamic behavior via a program demands two different activities. First, we must tease out those portions of our "world" that change over time or in reaction to actions, and we must develop a data representation D for this information. Keep in mind that a good data definition makes it easy for readers to map data to information in the real world and vice versa. For all others aspects of the world, we use global constants, including graphical or visual constants that are used in conjunction with the rendering operations.

Second, we must translate the "world" actions – the arrows in the above diagram – into interactions with the computer that the world teachpack can deal with. Once we have decided to use the passing of time for one aspect and mouse movements for another, we must develop functions that map the current state of the world – represented as data – into the next state of the world. Since the data definition D describes the class of data that represents the world, these functions have the following general contract and purpose statements:

| ; tick : D -> D |

| ; deal with the passing of time |

| (define (tick w) ...) |

| ; click : D Number Number MouseEvent -> D |

| ; deal with a mouse click at (x,y) of kind me |

| ; in the current world w |

| (define (click w x y me) ...) |

| ; control : D KeyEvent -> D |

| ; deal with a key event (symbol, char) ke |

| ; in the current world w |

| (define (control w ke) ...) |

That is, the contracts of the various hooks dictate what the contracts of these functions are once we have defined how to represent the world in data.

A typical program does not use all three of these actions and functions but often just one or two. Furthermore, the design of these functions provides only the top-level, initial design goal. It often demands the design of many auxiliary functions.

1.2.3.3 Simulating a Door: Data

Our first and immediate goal is to represent the world as data. In this specific example, the world consists of our door and what changes about the door is whether it is locked, unlocked but closed, or open. We use three symbols to represent the three states:

| ; DATA DEF. |

| ; The state of the door (SD) is one of: |

| ; – 'locked |

| ; – 'closed |

| ; – 'open |

Symbols are particularly well-suited here because they directly express the state of the door.

Now that we have a data definition, we must also decide which computer actions and interactions should model the various actions on the door. Our pictorial representation of the door’s states and transitions, specifically the arrow from "open" to "closed" suggests the use of a function that simulates time. For the other three arrows, we could use either keyboard events or mouse clicks or both. Our solution uses three keystrokes: #\u for unlocking the door, #\l for locking it, and #\space for pushing it open. We can express these choices graphically by translating the above "state machine" from the world of information into the world of data:

1.2.3.4 Simulating a Door: Functions

Our analysis and data definition leaves us with three functions to design:

automatic-closer, which closes the time during one tick;

door-actions, which manipulates the time in response to pressing a key; and

render, which translates the current state of the door into a visible scene.

Let’s start with automatic-closer. We know its contract and it is easy to refine the purpose statement, too:

| ; automatic-closer : SD -> SD |

| ; closes an open door over the period of one tick |

| (define (automatic-closer state-of-door) ...) |

Making up examples is trivial when the world can only be in one of three states:

given state

desired state

’locked

’locked

’closed

’closed

’open

’closed

| ; automatic-closer : SD -> SD |

| ; closes an open door over the period of one tick |

| (check-expect (automatic-closer 'locked) 'locked) |

| (check-expect (automatic-closer 'closed) 'closed) |

| (check-expect (automatic-closer 'open) 'closed) |

| (define (automatic-closer state-of-door) ...) |

The template step demands a conditional with three clauses:

| (define (automatic-closer state-of-door) |

| (cond |

| [(symbol=? 'locked state-of-door) ...] |

| [(symbol=? 'closed state-of-door) ...] |

| [(symbol=? 'open state-of-door) ...])) |

The examples basically dictate what the outcomes of the three cases must be:

| (define (automatic-closer state-of-door) |

| (cond |

| [(symbol=? 'locked state-of-door) 'locked] |

| [(symbol=? 'closed state-of-door) 'closed] |

| [(symbol=? 'open state-of-door) 'closed])) |

Don’t forget to run the example-tests.

For the remaining three arrows of the diagram, we design a function that reacts to the three chosen keyboard events. As mentioned, functions that deal with keyboard events consume both a world and a keyevent:

| ; door-actions : SD Keyevent -> SD |

| ; key events simulate actions on the door |

| (define (door-actions s k) ...) |

given state

given keyevent

desired state

’locked

#\u

’closed

’closed

#\l

’locked

’closed

#\space

’open

’open

–

’open

The examples combine what the above picture shows and the choices we made about mapping actions to keyboard events.

From here, it is straightforward to turn this into a complete design:

| (define (door-actions s k) |

| (cond |

| [(and (symbol=? 'locked s) (key=? #\u k)) 'closed] |

| [(and (symbol=? 'closed s) (key=? #\l k)) 'locked] |

| [(and (symbol=? 'closed s) (key=? #\space k)) 'open] |

| [else s])) |

| (check-expect (door-actions 'locked #\u) 'closed) |

| (check-expect (door-actions 'closed #\l) 'locked) |

| (check-expect (door-actions 'closed #\space) 'open) |

| (check-expect (door-actions 'open 'any) 'open) |

| (check-expect (door-actions 'closed 'any) 'closed) |

Last but not least we need a function that renders the current state of the world as a scene. For simplicity, let’s just use a large enough text for this purpose:

| ; render : SD -> Scene |

| ; translate the current state of the door into a large text |

| (define (render s) |

| (text (symbol->string s) 40 'red)) |

| (check-expecy (render 'closed) (text "closed" 40 'red)) |

Once everything is properly designed, it is time to run the program. In the case of the world teachpack, this means we must specify which function takes care of tick events, key events, and redraws:

| (big-bang 100 100 1 'locked) |

| (on-tick-event automatic-closer) |

| (on-key-event door-actions) |

| (on-redraw render) |

Now it’s time for you to collect the pieces and run them in DrRacket to see whether it all works.